Source of graph: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

Source of graph: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

(p. A1) Stark evidence that high medical payments do not necessarily buy high-quality patient care is presented in a hospital study set for release today.

In a Pennsylvania government survey of the state’s 60 hospitals that perform heart bypass surgery, the best-paid hospital received nearly $100,000, on average, for the operation while the least-paid got less than $20,000. At both, patients had comparable lengths of stay and death rates.

And among the 20 hospitals serving metropolitan Philadelphia, two of the highest paid actually had higher-than-expected death rates, the survey found.

Hospitals say there are numerous reasons for some of the high payments, including the fact that a single very expensive case can push up the averages.

Still, the Pennsylvania findings support a growing national consensus that as consumers, insurers and employers pay more for care, they are not necessarily getting better care. Expensive medicine may, in fact, be poor medicine.

“For most consumers, the fact that there is no connection between quality and cost is one of the dirty secrets of medicine,” said Peter V. Lee, the chief executive of the Pacific Business Group on Health, a California group of employers that provide health care coverage for workers.

. . .

(p. C4) And the survey found that good care can go unrewarded. One Philadelphia area hospital, Main Line Health’s Lankenau center, which performs a large number of bypass surgeries and has a high success rate, according to the survey, was paid an average of $33,549 by private insurers. That was less than half the nearly $80,000 in average payments received by the other hospitals, with poorer track records.

. . .

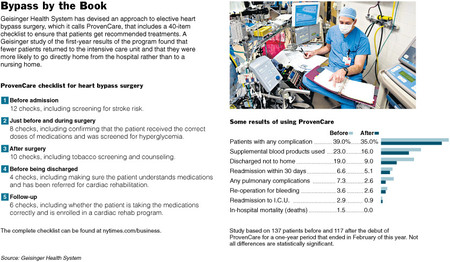

“The current reimbursement paradigm is fundamentally broken,” said Dr. Ronald Paulus, an executive with Geisinger, who says there is no current financial incentive for a hospital to provide the kind of care that leads to better outcomes and lower payments.

. . .

The problem, according to some health policy experts, is that the hospitals may, in fact, be rewarded for poor care: keeping patients too long because they caught an infrection or had a complication. That, they say, could be the main lesson of the Pennsylvania survey.

"What this highlights is the assumption that more money means better care is flat-out wrong," said Mr. Lee, the chief executive of the California employer group. "It’s easy to pay for bad quality, and we pay for it every day."

For the full story, see:

(Note: The last three paragraphs, and the last sentence of the fourth from the last paragraph, of the print version of the article, are missing from the online version.)

(Note: ellipses added.)

Source of graphic: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

Source of graphic: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

Source of graphic: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

Source of graphic: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.