The story quoted below tells how outsourcing high-tech jobs to India has bid up the salaries of high-tech Indian engineers, thereby reducing the appeal of further outsourcing. Marvelous how the market works!

Another lesson from the story applies to forecasting: mechanical extrapolation of current trends is inferior to prediction that takes account of predictable changes in prices (in this case, salaries).

(p. A15) Around the century’s turn, when U.S. companies first began flooding to India for its cheap labor, pundits warned that the subcontinent could increasingly rob the U.S. of high-end white-collar jobs. Debate was especially sharp in Silicon Valley, then in a slump, because India annually turns out nearly 500,000 engineering graduates.

. . .

Several years on, the forces of globalization are starting to even things out between the U.S. and India, in sophisticated technology work. As more U.S. tech companies poured in, they soaked up the pool of high-end engineers qualified to work at global companies, belying the notion of an unlimited supply of top Indian engineering talent. In a 2005 study, McKinsey & Co. estimated that just a quarter of India’s computer engineers had the language proficiency, cultural fit and practical skills to work at multinational companies.

The result is increasing competition for the most skilled Indian computer engineers and a narrowing U.S.-India gap in their compensation. India’s software-and-service association puts wage inflation in its industry at 10% to 15% a year. Some tech executives say it’s closer to 50%. In the U.S., wage inflation in the software sector is under 3%, according to Moody’s Economy.com.

Rafiq Dossani, a scholar at Stanford University’s Asia-Pacific Research Center who recently studied the Indian market, found that while most Indian technology workers’ wages remain low — an average $5,000 a year for a new engineer with little experience — the experienced engineers Silicon Valley companies covet can now cost $60,000 to $100,000 a year. “For the top-level talent, there’s an equalization,” he says.

For the full story, see:

Pui-Wing Tam and Jackie Range. “Second Thoughts: Some in Silicon Valley Begin to Sour on India; A Few Bring Jobs Back As Pay of Top Engineers In Bangalore Skyrockets.” Wall Street Journal (Tues., July 3, 2007): A1 & A15.

(Note: ellipsis added.)

Source of table: "World Publics Welcome Global Trade — But Not Immigration." Pew Global Attitudes Project, a project of the PewResearchCenter. Released: 10.04.07 dowloaded from:

Source of table: "World Publics Welcome Global Trade — But Not Immigration." Pew Global Attitudes Project, a project of the PewResearchCenter. Released: 10.04.07 dowloaded from:  Source of graphic: online version of the WSJ article cited below.

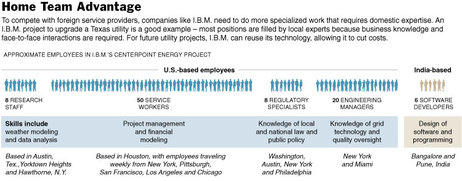

Source of graphic: online version of the WSJ article cited below.