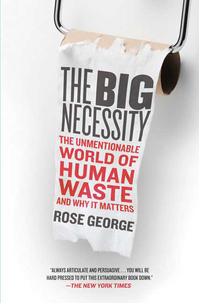

“A Kobe city official, left, visited Mitsue Watase, 100, at her home last week as Japanese officials started a survey on the whereabouts of centenarians.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below. Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

“A Kobe city official, left, visited Mitsue Watase, 100, at her home last week as Japanese officials started a survey on the whereabouts of centenarians.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below. Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

Oskar Morgenstern is mainly known as the co-author with John von Neumann of the book that started game theory. But it may be that his most important contribution to economics is a little known book called On the Accuracy of Economic Observations. In that book he gave examples of social scientists theorizing to explain ‘facts’ that turned out not to be true (such as the case of the 14 year-old male widowers).

The point is that truth would be served by economists spending a higher percent of their time in improving the quality of data.

One can imagine Morgenstern sadly smiling at the case of the missing Japanese centenarians:

(p. 1) TOKYO — Japan has long boasted of having many of the world’s oldest people — testament, many here say, to a society with a superior diet and a commitment to its elderly that is unrivaled in the West.

That was before the police found the body of a man thought to be one of Japan’s oldest, at 111 years, mummified in his bed, dead for more than three decades. His daughter, now 81, hid his death to continue collecting his monthly pension payments, the police said.

Alarmed, local governments began sending teams to check on other elderly residents. What they found so far has been anything but encouraging.

A woman thought to be Tokyo’s oldest, who would be 113, was last seen in the 1980s. Another woman, who would be the oldest in the world at 125, is also missing, and probably has been for a long time. When city officials tried to visit her at her registered address, they discovered that the site had been turned into a city park, in 1981.

To date, the authorities have been unable to find more than 281 Japanese who had been listed in records as 100 years old or older. Facing a growing public outcry, the (p. 6) country’s health minister, Akira Nagatsuma, said officials would meet with every person listed as 110 or older to verify that they are alive; Tokyo officials made the same promise for the 3,000 or so residents listed as 100 and up.

The national hand-wringing over the revelations has reached such proportions that the rising toll of people missing has merited daily, and mournful, media coverage. “Is this the reality of a longevity nation?” lamented an editorial last week in The Mainichi newspaper, one of Japan’s biggest dailies.

. . .

. . . officials admit that Japan may have far fewer centenarians than it thought.

“Living until 150 years old is impossible in the natural world,” said Akira Nemoto, director of the elderly services section of the Adachi ward office. “But it is not impossible in the world of Japanese public administration.”

For the full story, see:

MARTIN FACKLER. “Japan, Checking on Its Oldest People, Finds Many Gone, Some Long Gone.” The New York Times, First Section (Sun., August 15, 2010): 1 & 6.

(Note: ellipses added.)

(Note: the online version of the article is dated August 14, 2010 and has the somewhat shorter title “Japan, Checking on Its Oldest, Finds Many Gone”; the words “To date” appear in the online, but not the print, version of the article.)

The Morgenstern book is:

Morgenstern, Oskar. On the Accuracy of Economic Observations. 2nd ed. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1965.

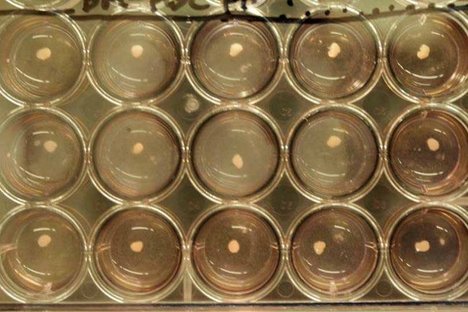

“Researchers from Japan used human stem cells to create “liver buds,” rudimentary livers that, when transplanted into mice, grew and functioned.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

“Researchers from Japan used human stem cells to create “liver buds,” rudimentary livers that, when transplanted into mice, grew and functioned.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.