Source of graph: http://www.equality-of-opportunity.org/

Source of graph: http://www.equality-of-opportunity.org/

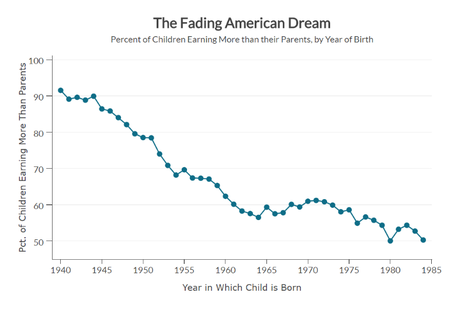

(p. 2) These days, people are arguably more worried about the American dream than at any point since the Depression. But there has been no real measure of it, despite all of the data available. No one has known how many Americans are more affluent than their parents were — and how the number has changed.

The beginnings of a breakthrough came several years ago, when a team of economists led by Raj Chetty received access to millions of tax records that stretched over decades. The records were anonymous and came with strict privacy rules, but nonetheless allowed for the linking of generations.

The resulting research is among the most eye-opening economics work in recent years.

. . .

After the research began appearing, I mentioned to Chetty, a Stanford professor, and his colleagues that I thought they had a chance to do something no one yet had: create an index of the American dream. It took them months of work, using old Census data to estimate long-ago decades, but they have done it. They’ve constructed a data set that shows the percentage of American children who earn more money — and less money — than their parents earned at the same age.

The index is deeply alarming. It’s a portrait of an economy that disappoints a huge number of people who have heard that they live in a country where life gets better, only to experience something quite different.

. . .

About 92 percent of 1940 babies had higher pretax inflation-adjusted household earnings at age 30 than their parents had at the same age.

. . .

For babies born in 1980 — today’s 36-year-olds — the index of the American dream has fallen to 50 percent: Only half of them make as much money as their parents did.

For the full commentary, see:

Leonhardt, David. “The American Dream, Quantified at Last.” The New York Times, SundayReview Section (Sun., DEC. 11, 2016): 2.

(Note: ellipses added.)

(Note: the online version of the commentary has the date DEC. 8, 2016.)

The Chetty co-authored paper mentioned above, is:

Chetty, Raj, David Grusky, Maximilian Hell, Nathaniel Hendren, Robert Manduca, and Jimmy Narang. “The Fading American Dream: Trends in Absolute Income Mobility since 1940.” Science 356, no. 6336 (2017): 398-406.