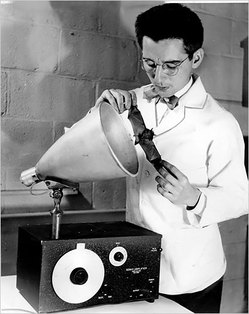

“Kenneth Rogoff and Carmen Reinhart at Ms. Reinhart’s Washington home. They started their book around 2003, years before the economy began to crumble.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

“Kenneth Rogoff and Carmen Reinhart at Ms. Reinhart’s Washington home. They started their book around 2003, years before the economy began to crumble.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

(p. 1) Like a pair of financial sleuths, Ms. Reinhart and her collaborator from Harvard, Kenneth S. Rogoff, have spent years investigating wreckage scattered across documents from nearly a millennium of economic crises and collapses. They have wandered the basements of rare-book libraries, riffled through monks’ yellowed journals and begged central banks worldwide for centuries-old debt records. And they have manually entered their findings, digit by digit, into one of the biggest spreadsheets you’ve ever seen.

Their handiwork is contained in their recent best seller, “This Time Is Different,” a quantitative reconstruction of hundreds of historical episodes in which perfectly smart people made perfectly disastrous decisions. It is a panoramic opus, both geographically and temporally, covering crises from 66 countries over the last 800 years.

The book, and Ms. Reinhart’s and Mr. Rogoff’s own professional journeys as economists, zero in on some of the broader shortcomings of their trade — thrown into harsh relief by economists’ widespread failure to anticipate or address the financial crisis that began in 2007.

“The mainstream of academic research in macroeconomics puts theoretical coherence and elegance first, and investigating the data second,” says Mr. Rogoff. For that reason, he says, much of the profession’s celebrated work “was not terribly useful in either predicting the financial crisis, or in assessing how it would it play out once it happened.”

“People almost pride themselves on not paying attention to current events,” he says.

. . .

(p. 6) Although their book is studiously nonideological, and is more focused on patterns than on policy recommendations, it has become fodder for the highly charged debate over the recent growth in government debt.

To bolster their calls for tightened government spending, budget hawks have cited the book’s warnings about the perils of escalating public and private debt. Left-leaning analysts have been quick to take issue with that argument, saying that fiscal austerity perpetuates joblessness, and have been attacking economists associated with it.

. . .

The economics profession generally began turning away from empirical work in the early 1970s. Around that time, economists fell in love with theoretical constructs, a shift that has no single explanation. Some analysts say it may reflect economists’ desire to be seen as scientists who describe and discover universal laws of nature.

“Economists have physics envy,” says Richard Sylla, a financial historian at the Stern School of Business at New York University. He argues that Paul Samuelson, the Nobel laureate whom many credit with endowing economists with a mathematical tool kit, “showed that a lot of physical theories and concepts had economic analogs.”

Since that time, he says, “economists like to think that there is some physical, stable state of the world if they get the model right.” But, he adds, “there is really no such thing as a stable state for the economy.”

Others suggest that incentives for young economists to publish in journals and gain tenure predispose them to pursue technical wizardry over deep empirical research and to choose narrow slices of topics. Historians, on the other hand, are more likely to focus on more comprehensive subjects — that is, the material for books — that reflect a deeply experienced, broadly informed sense of judgment.

“They say historians peak in their 50s, once they’ve accumulated enough knowledge and wisdom to know what to look for,” says Mr. Rogoff. “By contrast, economists seem to peak much earlier. It’s hard to find an important paper written by an economist after 40.”

For the full story, see:

CATHERINE RAMPELL. “They Did Their Homework (800 Years of It).” The New York Times, SundayBusiness Section (Sun., July 4, 2010): 1 & 6.

(Note: the online version of the article is dated July 2, 2010.)

(Note: ellipses added.)

The reference for the book is:

Reinhart, Carmen M., and Kenneth Rogoff. This Time Is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2009.

Source of book image: http://www.paschaldonohoe.ie/wp-content/uploads/2010/02/This-time-is-different.jpg