Cooling towers at the Vogtle nuclear power plant in Georgia. Source of photo: the online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

Cooling towers at the Vogtle nuclear power plant in Georgia. Source of photo: the online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

A long, and informative cover-story in the NYT, discusses the costs and benefits of nuclear power. My read is that, on balance, the considerations in the article favor nuclear energy. Here are a few passages from near the end of the article:

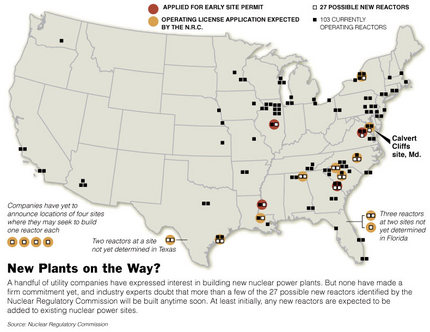

(p. 64) Gary Taylor, . . ., the C.E.O. of Entergy Nuclear, says he believes a doubling of the number of nuclear plants around the world is inevitable, both to satisfy energy demands and to counter global warming. As Taylor puts it: ”The reality is, what is scalable in the time frame that addresses the issues? If it isn’t this technology, I don’t know what it would be.” Diaz, the former head of the N.R.C., told me he sees a similarly bright future for nuclear. ”The world is going to go nuclear, because they do not have any other real alternatives,” he says. I met plenty of other engineers within the industry who went even further. Their feeling about nuclear power is close to evangelical, in that they seem to approach the technology with moral certitude while being loath to acknowledge any of its many negatives. Would that include the utility executives who will ultimately decide if — and what — to build? I’m not sure it would. To those I spoke with in the uppermost ranks, nuclear power isn’t a belief system. It’s a business. And to them, what might come out of, say, Vogtle Units 3 and 4 — the waste and the power and the profits — would be nearly identical to what comes out of Units 1 and 2.

At least that was my conclusion in Georgia, where Jeff Gasser, the Southern Company’s chief nuclear officer, took me through a long tour of the plant. He was smart, meticulous and intensely committed to the obscure safety protocols that go on at nuclear power facilities. Most of all he was forthright about the advantages and disadvantages of the nukes business. When we went to visit the spent-fuel pool in Vogtle, where the used fuel-rod assemblies are stored under 20 feet of protective water, Gasser let me know that we would die if we pulled one of the fuel assemblies out of the pool. ”We would receive, before we could get to the exit door a few feet away, a lethal radiation dose,” he said. I quickly had to check the radiation dosimeter I was wearing — another legal requirement of the N.R.C. — to see if I was already glowing. (It read zero.) ”The communications people hate it when I use words like ‘lethal’ and ‘irradiated,’ ” Gasser continued. ”But the fact is, there is no perfect way of generating electricity. There are byproducts for every type.” Like many others, he went through the positives and negatives of coal, gas, solar, wind and nuclear. In his opinion, he added, with Vogtle’s engineering, redundancy of safety systems and its trained operators, it was a safe, reliable and efficient way of making electricity. That was his sales pitch.

We had already passed through the containment buildings, where the reactors heat the pressurized water. So Gasser took me through the turbine building, an enormous room the size of a soccer field, where the steam turns the fan blades. Eventually, we went out a back door into the sunlight. The deafening sounds of turbines and machinery subsided to a dull thrum. We removed our earplugs and walked over to a small forest of electrical transformers, our backs to the plant. The electricity from the turbines inside comes out here, Gasser explained, its voltage is transformed, and it is then put into the grid.

Gasser made a pushing motion toward the green hills before us.

”Once the power is sent out of here, it can go everywhere,” he explained. And I could see that it did go everywhere. The high-tension wires stretched away from where we stood, in several directions, through deep cuts in the pinelands, as far as I could see.

For the full article, see:

JON GERTNER. "Atomic Balm? ‘ The New York Times Magazine, Section 6 (Sunday, July 16, 2006), 36-47, 56, 62 & 64.

Yellowcake, which is processed uranium, is in the third jar from the left of the top photo. The photo below it is of old equipment at a dormant uranium mine. Source of the photos and the graphic: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.

Yellowcake, which is processed uranium, is in the third jar from the left of the top photo. The photo below it is of old equipment at a dormant uranium mine. Source of the photos and the graphic: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.

Cooling towers at the Vogtle nuclear power plant in Georgia. Source of photo: the online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

Cooling towers at the Vogtle nuclear power plant in Georgia. Source of photo: the online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

Patrick Moore, co-founder of Greenpeace. Source of image:

Patrick Moore, co-founder of Greenpeace. Source of image: