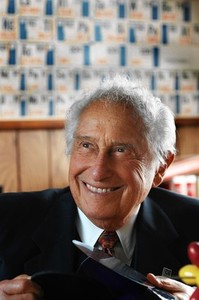

“Judge Richard Posner.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the WSJ article quoted and cited below.

I am deeply conflicted about patents. On the one hand, property rights are important, both ethically and in terms of economic incentives. On the other hand, patents seem to restrict innovation.

The views of Posner are worth serious consideration. My own current view is that the patent rules need to be reformed and their implementation made more efficient. But I do not think the patent system should be abolished.

(p. B1) While technology companies continue to fight over smartphone patents, one judge has fought his way into the ring.

He is 73-year-old Richard Posner, among the most potent forces on the federal bench and an outspoken critic of the patent system.

Presiding over a lawsuit between Apple Inc. . . . and Google Inc.’s . . . Motorola Mobility in June, he dropped a bombshell, scrapping the entire case and preventing the companies from refiling their claims. The ruling startled the litigants in the case and fueled a national discussion about whether the patent system (p. B5) is broken.

. . .

In the June ruling, explaining why he wouldn’t ban Motorola products from the shelves, Judge Posner said: “An injunction that imposes greater costs on the defendant than it confers benefits on the plaintiff reduces net social welfare.”

Judge Posner, who declined to be interviewed for this article, has continued to press the issue.

This month, he wrote an essay in the Atlantic headlined, “Why There Are Too Many Patents In America.” He said “most industries could get along fine without patent protection” and that the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office has done a woeful job, calling it “understaffed,” and “many patent examinations…perfunctory.”

He saved ammunition for juries and fellow jurists. “Judges have difficulty understanding modern technology and jurors have even greater difficulty,” he wrote. He suggested several reforms to the patent system, including shortening the patent term for inventors in some industries and expanding the authority of the Patent and Trademark Office to try patents cases.

. . .

Judge Posner’s intellectual curiosity is well-known and “people assume he has no political ax to grind because he’s not trying to advance the fortunes of any particular segment of the economy,” said Arthur D. Hellman, a law professor at University of Pittsburgh who studies the judiciary.

Yet his ruling poses a difficult question for the Federal Circuit Court of Appeals, the specialized one that handles intellectual property cases, about whether infringement matters without damages.

Peter Menell, a law professor at UC Berkeley, likened it to the old thought experiment that begins “If a tree falls in the woods.” He said: “If there are no damages, do you need to have a trial?”

Juge Posner also rejected Google’s bid to block the sale of iPhones that allegedly infringed a so-called “standards-essential patent” owned by Google. Standards-essential patents protect innovations used in technologies that industries collectively agree to use, like Wi-Fi or 3G. A company that holds one of these patents stands to profit enormously, because its competitors have to pay it for licenses to use the technology.

But Judge Posner ruled that holders of such patents aren’t entitled to injunctions. Michael Carrier, a law professor at Rutgers University, Camden, said the opinion on standards-essential patents came amid a groundswell of opposition to injunctions for such patents and could put an end to the practice among U.S. federal judges.

For the full story, see:

JOE PALAZZOLO and ASHBY JONES. “Also on Trial: A Judge’s Worldview.” The Wall Street Journal (Tues., July 24, 2012): B1 & B5.

(Note: all ellipses were added except for the one internal to the quote from Judge Posner’s Atlantic blog posting.)

(Note: the online version of the article has the date July 23, 2012 and has the title “Apple and Samsung Patent Suit Puts Judge Posner’s Worldview on Trial.” The print version of the title could be interpreted as a sub-title of the main title to the accompanying adjacent article. The title of the main article was “Apple v. Samsung; In Silicon Valley, Patents Go on Trial.” The last two paragraphs above appear only in the online, but not in the print, version of the article.)

The Atlantic blog posting by Posner can be found at:

Posner, Richard A. “Why There Are Too Many Patents in America.” In The Atlantic blog, posted on July 12, 2012 at: http://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2012/07/why-there-are-too-many-patents-in-america/259725/.

(Note: the WSJ article above implies that the Posner essay was published in the print version of The Atlantic, but I can only find it in Posner’s blog on The Atlantic web site.)