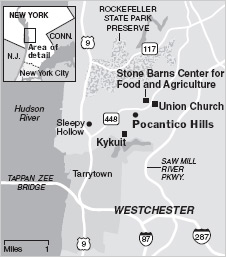

(p. D1) THE tranquil hamlet of Pocantico Hills, N.Y., has been bound up with the Rockefellers for more than a century. The family’s imprint is everywhere: In the thousands of acres of nearby pastures, woodlands and lakes that John D. Rockefeller Sr. began acquiring as he created his family’s estate in the 1890s. In the august stone walls enclosing a collection of even more august mansions. And in the stunning stained-glass windows by Matisse and Chagall that grace a simple stone church.

The Rockefellers are still an active presence — David Rockefeller, who at 91 is the last of the “brothers” from the illustrious third generation, spends weekends at his farm, Hudson Pines, and still rides in his horse-drawn carriage over the graceful carriage roads designed by his father and grandfather. A number of other Rockefellers — including Happy, the widow of David’s brother Nelson, the former governor and vice president — have houses on the family land as well.

Much of the Rockefeller family’s business and pleasure in and around Pocantico Hills is, not surprisingly, out of view. But the tradition of philanthropy that has defined the clan as much as its vast fortune also operates there. The result is a sense of shared bounty.

The public has long been allowed to enjoy the Rockefellers’ 55 miles of carriage roads, which also function as hiking trails, and the opportunity to experience Rockefeller country grew with the creation of the Rockefeller State Park Preserve. Its 1,384 acres are used for hiking, horseback riding and carriage driving. . . .

. . .

(p. D5) A visitor can hike quiet trails evoking the family’s legacy, with names like Peggy’s Way and Brothers’ Path, and then have lunch in a smartly rustic cafe at Stone Barns — or an elegant dinner at Blue Hill. And while tours of Union Church of Pocantico Hills, with its Chagall and Matisse windows, will not resume until early April, anyone can attend Sunday morning services at 9 and 11. (But be discreet: the pastor, the Rev. Dr. F. Paul DeHoff, noted on the phone that services were for worship, not window viewing.)

. . .

The rose window over the altar was dedicated on Mother’s Day 1956 in memory of Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, John D. Jr.’s wife. Mrs. Rockefeller, a co-founder of the Museum of Modern Art, collected contemporary art, including works by Matisse. The head of the museum at the time suggested Matisse, then in his 80s, for the memorial window, and approached the artist on the family’s behalf.

Matisse accepted the commission, which turned out to be his last. The paper cutouts he used to design the blue, green and yellow window were in his bedroom when he died.

A much larger window at the rear of the church, by Marc Chagall, celebrates the life of John D. Rockefeller Jr., who died in 1960. The window tells the biblical story of the good Samaritan in brilliant blues and greens, echoing Matisse’s window.

Unlike Matisse, Chagall traveled to Pocantico Hills to see the church. At the dedication, Chagall broached the subject of the lackluster nave windows. He received a commission to redo all eight, including one in memory of Nelson Rockefeller’s son, Michael, who died in New Guinea in 1961.

If the memorial windows represent an extraordinary gift of culture in an unlikely nook of Westchester, the family’s present of the state park preserve was equally significant — a chunk of green space one and a half times the size of Central Park.

A good winter hike in the preserve is along Eagle Hill Trail, a steep ascent that offers panoramic views of the Hudson, farmland and Kykuit. Another scenic walk is on Brothers’ Path, which runs next to Swan Lake near the visitors’ center. Brothers’ Path connects to Brook Trail, which crosses a half-frozen stream: water bubbles beneath thin sheets of ice and the dazzling snow frames dark pools of water.

![]() Source of graphic: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

Source of graphic: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

Source of map: online version of the NYT article cited above.

Source of map: online version of the NYT article cited above.

Upper left is a carriage road in Rockefeller country; upper right is a Marck Chagall window in Union Church; lower left is a map of Rockefeller country. Source of photos and map: online version of the NYT article cited above.

Upper left is a carriage road in Rockefeller country; upper right is a Marck Chagall window in Union Church; lower left is a map of Rockefeller country. Source of photos and map: online version of the NYT article cited above. Source of image: online version of WSJ article cited below.

Source of image: online version of WSJ article cited below.

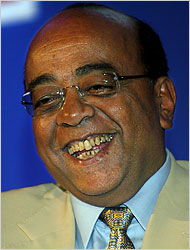

Billionaire entrepreneur Mo Ibrahim. Source of photo: online version of the NYT article cited below.

Billionaire entrepreneur Mo Ibrahim. Source of photo: online version of the NYT article cited below.  The Flagler Memorial obelisk was erected in on a man-made island in 1920, when Miamians still remembered the accomplishments of Henry Flagler. Source of image:

The Flagler Memorial obelisk was erected in on a man-made island in 1920, when Miamians still remembered the accomplishments of Henry Flagler. Source of image: