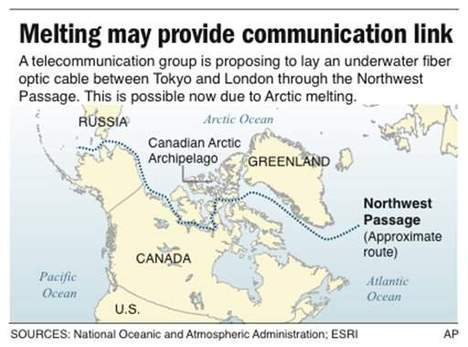

Source of map: online version of the Omaha World-Herald article quoted and cited below.

Source of map: online version of the Omaha World-Herald article quoted and cited below.

(p. 4A) ANCHORAGE, Alaska (AP) – Global warming has melted so much Arctic ice that a telecommunication group is moving forward with a project that was unthinkable just a few years ago: laying underwater fiber optic cable between Tokyo and London by way of the Northwest Passage.

The proposed system would nearly cut in half the time it takes to send messages from the United Kingdom to Asia, said Walt Ebell, CEO of Kodiak-Kenai Cable Co. The route is the shortest underwater path between Tokyo and London.

The quicker transmission time is important in the financial world where milliseconds can count in executing profitable trades and transactions. “Speed is the crux,” Ebell said. “You’re cutting the delay from 140 milliseconds to 88 milliseconds.”

. . .

“It will provide the domestic market an alternative route not only to Europe – there’s lots of cable across the Atlantic – but it will provide the East Coast with an alternative, faster route to Asia as well,” he said.

The cable would pass mostly through U.S., Canadian international waters and avoid possible trouble spots along the way.

“You’re not susceptible to ‘events,’ I should say, that you might run into with a cable that runs across Russia or the cables that run down around Asia and go up through the Suez Canal into the Mediterranean Sea. You’re getting away from those choke points.”

For the full story, see:

DAN JOLING, Associated Press Writer. “Loss of Arctic Ice Opens Up New Cable Route.” Omaha World-Herald (Fri., January 22, 2010): 4A.

(Note: the online version of the article had the title: Global warming opens up Arctic for undersea cable” and was dated January 21, 2010.)

(Note: ellipsis added.)