“In the vegetable garden at Monticello, his home in Virginia, Thomas Jefferson sowed seeds from around the world and shared them with farmers. He was not afraid of failure, which happened often.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

“In the vegetable garden at Monticello, his home in Virginia, Thomas Jefferson sowed seeds from around the world and shared them with farmers. He was not afraid of failure, which happened often.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

Steven Johnson has written an intriguing argument that the intellectual foundation of the founding fathers was based as much on experimental science as on religion. The article quoted below provides a small bit of additional evidence in support of Johnson’s argument.

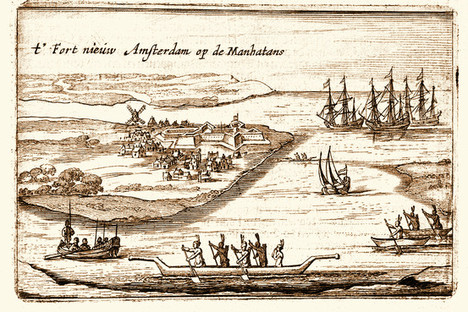

(p. D1) NEW gardeners smitten with the experience of growing their own food — amazed at the miracle of harvesting figs on a Brooklyn rooftop, horrified by the flea beetles devouring the eggplants — might be both inspired and comforted by the highs and lows recorded by Thomas Jefferson from the sun-baked terraces of his two-acre kitchen garden 200 years ago.

And they could learn a thing or two from the 19th-century techniques still being used at Monticello today.

“He was experimental and had a lot of failures,” Peter Hatch, the director of gardens and grounds, said on a recent afternoon, as we stood under a scorching sun in the terraced garden that took seven slaves three years to cut into the hill. “But Jefferson always believed that ‘the failure of one thing is repaired by the success of another.’ ”

After he left the White House in 1809 and moved to Monticello, his Palladian estate here, Jefferson grew 170 varieties of fruits and 330 varieties of vegetables and herbs, until his death in 1826.

As we walked along the geometric beds — many of them planted in an ancient Roman quincunx pattern — I made notes on the beautiful crops I had never grown. Sea kale, with its great, ruffled blue-green leaves, now full of little round seed pods. Egyptian onions, whose tall green stalks bore quirky hats of tiny seeds and wavy green sprouts. A pre-Columbian tomato called Purple Calabash, whose energetic vines would soon be trained up a cedar trellis made of posts cut from the woods.

“Purple Calabash is one of my favorites,” Mr. Hatch said. “It’s an acidic, al-(p. D7)most black tomato, with a convoluted, heavily lobed shape.”

Mr. Hatch, who has directed the restoration of the gardens here since 1979, has pored over Jefferson’s garden notes and correspondence. He has distilled that knowledge in “Thomas Jefferson’s Revolutionary Garden,” to be published by Yale University Press.

For the full story, see:

ANNE RAVER. “A Revolutionary With Seeds, Too.” The New York Times (Thurs., July 1, 2010): D1 & D7.

(Note: the online version of the article is dated June 30, 2010 and has the title “In the Garden; At Monticello, Jefferson’s Methods Endure.”)