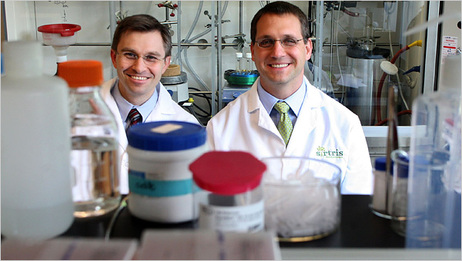

"Eric von Hippel of M.I.T., left, and Dr. Nathaniel Sims, with hospital devices Dr. Sims has modified. Mr. von Hippel says users can improve on products." Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article cited below.

"Eric von Hippel of M.I.T., left, and Dr. Nathaniel Sims, with hospital devices Dr. Sims has modified. Mr. von Hippel says users can improve on products." Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article cited below.

Some innovation is done by the devoted for free. But in his books, and in the article excerpted below, I think von Hippel puts too little emphasis on the entrepreneur and the entrepreneur’s profit motive, as drivers of innovation.

One example is the Moveable Type free program that underlies this, and many other blogs. It is often described as one of the best blog platforms, but it is hard to use for a non-techie, kludgey, and very limited in some obvious ways. For example, there apparently is no way that I can make comments to the most recent 10 entries visible on the main blog page. And there is only limited backup capabilities. And the spell-checker does not have "blog" in its dictionary, and asks me if I really meant to type "bog."

You can bet that if Moveable Type was produced for profit, they would have provided users these obvious capabilities. And I would rather pay for a more capable program, rather than get a less capable program for free.

(p. 5) DR. NATHANIEL SIMS, an anesthesiologist at Massachusetts General Hospital, has figured out a few ways to help save patients’ lives.

In doing so, he also represents a significant untapped vein of innovation for companies.

Dr. Sims has picked up more than 10 patents for medical devices over his career. He ginned up a way to more easily shuttle around the dozen or more monitors and drug-delivery devices attached to any cardiac patient after surgery, with a device known around the hospital as the “Nat Rack.”

. . .

What Dr. Sims did is called user-driven innovation by Eric von Hippel, a professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Sloan School of Management. Mr. von Hippel is the leading advocate of the value of letting users of products modify them or improve them, because they may come up with changes that manufacturers never considered. He thinks that this could help companies develop products more quickly and inexpensively than with their internal design teams.

“It could drive manufacturers out of the design space,” Mr. von Hippel says.

It is a difficult idea for research and development departments to accept, but one of his studies found that 82 percent of new capabilities for scientific instruments like electron microscopes were developed by users.

. . .

One problem with the user-innovation model is that it can run into intellectual property rights protections. . . .

. . .

. . . , Mr. von Hippel’s ideas are up against more conventional forms of user-aided design, such as sending anthropologists to study how people use products in their daily lives. Companies then translate their research into new designs.

Even some of Mr. von Hippel’s acolytes remain cautious. “A lot of this is still in the category of, ‘You could imagine this working out really well,’ ” says Saul T. Griffith, who as an M.I.T. engineering student was part of a group of kite-surfers who developed products for their sport that have since become commercialized. Mr. von Hippel wrote about Mr. Griffith in his 2005 book, “Democratizing Innovation.”

For the full story, see:

MICHAEL FITZGERALD. "Prototype How to Improve It? Ask Those Who Use It." The New York Times, Section 3 (Sun., March 25, 2007): 5.

(Note: ellipses added.)

von Hippel has two main books in which he defends his user-driven innovation ideas:

von Hippel, Eric. The Sources of Innovation. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988.

von Hippel, Eric. Democratizing Innovation. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2005.

"Patients at the Ramón Pando Ferrer eye hospital in Havana." Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

"Patients at the Ramón Pando Ferrer eye hospital in Havana." Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

"He took the subway, top, to travel to the apartment of a patient, Kayla McDermott, who had a sore throat." Source of caption and photos: online version of the NYT article cited above.

"He took the subway, top, to travel to the apartment of a patient, Kayla McDermott, who had a sore throat." Source of caption and photos: online version of the NYT article cited above. Sally Satel is a medical doctor and a resident scholar at the Amerrican Enterprise Institute. Source of photo:

Sally Satel is a medical doctor and a resident scholar at the Amerrican Enterprise Institute. Source of photo:  Source of graphic: online version of the NYT article cited below.

Source of graphic: online version of the NYT article cited below.

In the photo immediately above, Don and Andrea Steirle work in their lab. The map to the left shows the location of the Berkeley Pit. Source of the photo and map: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.

In the photo immediately above, Don and Andrea Steirle work in their lab. The map to the left shows the location of the Berkeley Pit. Source of the photo and map: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.