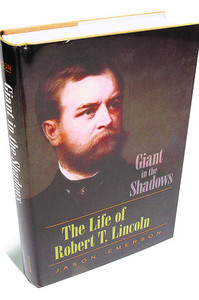

Source of book image: http://www.vtmagazine.vt.edu/fall06/news.html

(p. 5) IN the wake of widespread violence during the New York City blackout of 1977, a newspaper columnist quipped that just one flick of a light switch separated civilization from primordial chaos.

Leaving the hyperbole aside, artificial illumination has arguably been the greatest symbol of modern progress. By making nighttime infinitely more inviting, street lighting — gas lamps beginning in the early 1800s followed by electric lights toward the end of the century — drastically expanded the boundaries of everyday life to include hours once shrouded in darkness. Today, any number of metropolitan areas in the United States and abroad, bathed in the glare of neon and mercury vapor, bill themselves as 24-hour cities, open both for business and pleasure.

. . .

. . . there was never any question that 19th-century communities welcomed lamps, which in conjunction with police forces, posed a powerful deterrent to lawlessness. Another benefit lay in the numerous pedestrians drawn by their inviting glow, whose very presence helped to discourage crime.

“As safe and agreeable to walk out in the evening as by day-light,” pronounced a New Yorker in 1853.

Certainly, public anxiety over the recent removal of lamps should not be minimized. No longer are there witches and wolves to fear, but research strongly suggests, as one might expect, the critical value of street lighting as a hindrance to crime and serious accidents.

. . .

Financial costs and public safety, however, are not the only issues. Without the benefit of street lighting, towns and cities, after sunset, will be diminished as communities. Families will be more apt to “cocoon” at home, rather than visit friends or attend sporting and cultural events. And, too, our appreciation for night itself will suffer. Evenings can be best enjoyed if they remain inviting and safe, whether for neighborhood gatherings, walking Fido or gazing at the heavens — all with less chance of losing your wallet or stumbling into a ditch.

For the full commentary, see:

A. ROGER EKIRCH. “OPINION; Return to a Darker Age.” The New York Times, SundayReview Section (Sun., January 8, 2012): 5.

(Note: ellipses added.)

(Note: the online version of the commentary has the date January 7, 2012.)

Ekrich wrote a related book:

A. Roger Ekirch. At Day’s Close: Night in Times Past. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2005.